In the quiet streets of 19th century Copenhagen walked a solitary figure whose profound insights would eventually reshape Western philosophy. Søren Kierkegaard (1813-1855), often hailed as the “Father of Existentialism,” developed a philosophical approach centered on individual existence, subjective truth, and personal choice that would influence generations of thinkers. Though largely unrecognized during his lifetime, his penetrating analysis of human existence, religious faith, and authentic living would later inspire philosophers, theologians, psychologists, and writers across the globe. This biographical exploration traces the life journey of this remarkable Danish thinker whose work continues to challenge and illuminate our understanding of what it means to exist as an individual in an often impersonal world.

Early Life and Background

Søren Aabye Kierkegaard was born on May 5, 1813, in Copenhagen, Denmark. He entered the world during a tumultuous period of European history, as the Napoleonic Wars were reshaping the continent’s political landscape. Denmark itself was experiencing financial crisis, having declared state bankruptcy the same year. Yet the Kierkegaard household, situated in the heart of Copenhagen, enjoyed relative prosperity thanks to his father’s successful career as a wool merchant.

Family Dynamics and Religious Upbringing

Kierkegaard was the youngest of seven children born to Michael Pedersen Kierkegaard and his second wife, Ane Sørensdatter Lund. Michael Kierkegaard was a deeply religious man whose piety was tinged with melancholy. Having risen from poverty as a shepherd boy in Jutland to become a wealthy merchant in Copenhagen, the elder Kierkegaard carried a profound sense of guilt throughout his life. He believed he had brought God’s wrath upon himself and his family through past sins, including cursing God as a young man and having conceived his first child with Ane before marriage.

This sense of divine judgment cast a long shadow over the Kierkegaard household. Michael was convinced that all his children would die before the age of 34 (the age of Christ at crucifixion). Remarkably, five of his seven children did indeed die before he did, though Søren and his older brother Peter Christian outlived their father. This atmosphere of religious intensity, melancholy, and foreboding profoundly shaped young Søren’s psychological and spiritual development.

“I had real Christian satisfaction in the thought that, if there were no other, there was definitely one man in Copenhagen whom every poor person could freely accost and converse with on the street; that, if there were no other, there was one man who, whatever the society he most commonly frequented, did not shun contact with the poor, but greeted every maidservant he was acquainted with, every manservant, every common laborer.”

Despite the somber religious atmosphere at home, Kierkegaard later recalled his father with deep affection and respect. Michael Kierkegaard was not only pious but also intellectually curious, introducing his son to philosophical and theological discussions from an early age. These father-son dialogues, often extending late into the night, cultivated Søren’s remarkable intellectual abilities and his lifelong preoccupation with religious questions.

Education at the University of Copenhagen

Kierkegaard received his early education at the prestigious School of Civic Virtue in Copenhagen, where he studied Latin, Greek, history, and religion. Though not particularly distinguished among his peers, he displayed a sharp intellect and a talent for dialectical thinking. His classmates remembered him as somewhat eccentric, with a caustic wit that he often deployed as a defense mechanism against teasing about his slight, awkward physical appearance.

In 1830, Kierkegaard enrolled at the University of Copenhagen to study theology, following his father’s wishes. However, his academic interests soon expanded to include philosophy and literature. During his university years, Kierkegaard lived something of a double life—outwardly participating in Copenhagen’s social scene while inwardly wrestling with profound questions of faith, existence, and his own melancholic nature.

His university studies were interrupted by periods of apparent aimlessness and what he later called “dissipation.” Yet even during these times, Kierkegaard was developing the intellectual foundations that would later inform his philosophical work. He was particularly influenced by the writings of Socrates, Plato, G.W.F. Hegel, and the German Romantics, as well as by his philosophy professor Poul Martin Møller.

After his father’s death in 1838, Kierkegaard returned to his studies with renewed focus, completing his degree in theology in 1840 and earning a master’s degree (equivalent to a doctorate) in philosophy in 1841. His dissertation, “On the Concept of Irony with Continual Reference to Socrates,” already displayed the originality of thought and literary style that would characterize his later works.

Philosophical Journey

Kierkegaard’s philosophical development was marked by extraordinary productivity, particularly during the early 1840s when he published a series of works that would establish the foundation of existentialist thought. Unlike systematic philosophers who sought to build comprehensive theoretical frameworks, Kierkegaard focused on the concrete reality of individual human existence. His approach was deliberately unsystematic, often employing pseudonyms, irony, and indirect communication to engage readers in a process of self-reflection.

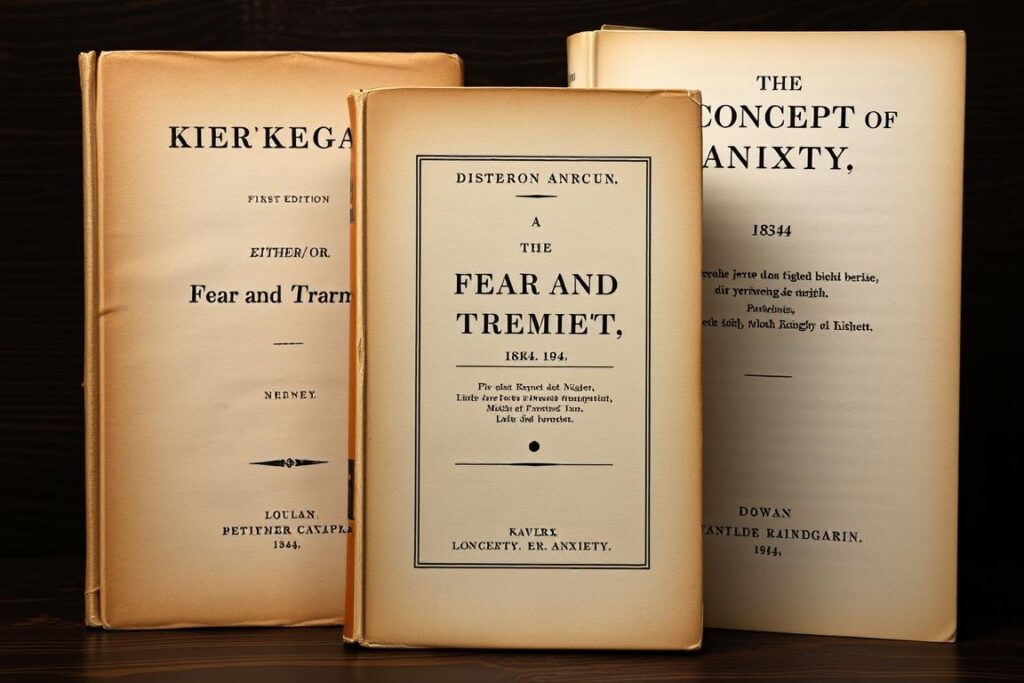

Analysis of Major Works

These works, along with others like Philosophical Fragments (1844), Stages on Life’s Way (1845), and Concluding Unscientific Postscript (1846), form what Kierkegaard called his “aesthetic authorship.” During this same period, he also published a series of Edifying Discourses under his own name, revealing the explicitly Christian dimension of his thought that ran parallel to his pseudonymous writings.

Key Philosophical Concepts

Subjectivity as Truth

One of Kierkegaard’s most influential ideas is his assertion that “truth is subjectivity.” This does not mean that objective truth doesn’t exist, but rather that the most important truths—particularly religious truths—cannot be known through detached, objective reasoning. Instead, they must be appropriated through passionate, personal engagement.

“What I really need is to get clear about what I must do, not what I must know, except insofar as knowledge must precede every act. What matters is to find a purpose, to see what it really is that God wills that I shall do; the crucial thing is to find a truth which is truth for me, to find the idea for which I am willing to live and die.”

In Concluding Unscientific Postscript, Kierkegaard (through his pseudonym Johannes Climacus) argues that objective certainty about religious matters is impossible and ultimately irrelevant. What matters is not whether Christianity is objectively true, but how one relates to it existentially. This emphasis on personal appropriation of truth stands in stark contrast to the Hegelian system that dominated philosophical discourse in Kierkegaard’s time.

The Leap of Faith

Perhaps Kierkegaard’s most famous concept is the “leap of faith.” Though he never used this exact phrase, the idea permeates his work, particularly in Fear and Trembling and Concluding Unscientific Postscript. For Kierkegaard, faith is not a matter of gradually accumulating evidence until belief becomes reasonable. Rather, it involves a decisive commitment in the face of objective uncertainty.

The leap of faith is not blind or irrational, but it does transcend the limits of reason. It acknowledges that some truths—particularly those concerning our relationship with God—cannot be approached through detached reasoning alone. Faith requires risk, courage, and what Kierkegaard calls “infinite passion.” It is an existential commitment of the whole person, not merely an intellectual assent to propositions.

Three Stages of Existence

Kierkegaard outlined three distinct “stages” or “spheres” of existence that represent different approaches to life:

The Aesthetic Stage

The aesthetic individual lives for pleasure and immediate gratification, avoiding commitment and seeking novelty to escape boredom. This stage is characterized by sensual enjoyment, intellectual detachment, and an emphasis on possibility rather than actuality. The aesthete ultimately falls into despair as the pursuit of pleasure proves empty and unsustainable.

The Ethical Stage

The ethical individual embraces universal moral norms and social responsibilities. This stage involves commitment to duties, marriage, career, and civic obligations. While more fulfilling than the aesthetic life, the ethical stage still falls short because it cannot account for the individual’s relationship to the absolute (God) and cannot overcome the problem of sin.

The Religious Stage

The religious individual relates directly to God through faith. Kierkegaard further divides this stage into “Religiousness A” (general religious consciousness) and “Religiousness B” (specifically Christian faith). The latter involves acknowledging the paradox of the eternal entering time through Christ’s incarnation and embracing this paradox through faith rather than reason.

These stages are not simply sequential steps in development but represent qualitatively different existential orientations. Movement between stages occurs not through gradual progression but through decisive “leaps” that involve radical reorientations of one’s entire existence.

Critique of Hegelianism and Systematic Philosophy

Throughout his works, Kierkegaard mounted a sustained critique of G.W.F. Hegel’s philosophical system, which dominated European intellectual life during his time. While Kierkegaard’s relationship to Hegel was complex and not entirely negative, he fundamentally rejected Hegel’s attempt to construct a comprehensive system that could explain all of reality through rational concepts.

For Kierkegaard, Hegel’s system failed to account for the concrete reality of individual existence. No abstract system could capture the passionate inwardness of human subjectivity or the paradoxical nature of Christian faith. As he famously noted, “System and finality correspond to one another, but existence is precisely the opposite of finality.”

This critique of systematic philosophy extended beyond Hegel to encompass the broader tendency in modern thought to prioritize abstract reasoning over lived experience. Kierkegaard insisted that the most important truths could not be communicated directly through philosophical systems but had to be approached indirectly through stories, parables, and existential engagement.

Personal Struggles

Kierkegaard’s philosophical insights were deeply intertwined with his personal struggles. His life was marked by profound inner conflicts, social isolation, and a sense of divine calling that often set him at odds with his contemporaries. These personal experiences were not incidental to his philosophy but constituted the existential ground from which his thinking emerged.

Broken Engagement with Regine Olsen

One of the most significant events in Kierkegaard’s personal life was his engagement to Regine Olsen in September 1840 and his subsequent breaking of that engagement approximately one year later. Regine was the daughter of a state official, and at 18 years old when they became engaged, she was ten years Kierkegaard’s junior.

The reasons for Kierkegaard’s decision to break the engagement remain somewhat mysterious. In his journals, he suggests various motivations: his melancholic temperament made him unsuitable for marriage; he harbored a dark secret he could not share with her; his religious calling demanded a solitary life; or perhaps he feared that domestic happiness would blunt the edge of his intellectual and spiritual pursuits.

“I was a penitent, and she was an innocent child who loved me with all her heart. I had to choose between two things: either to try to contribute to her unhappiness, or to try to make her happy by committing a sin against the holy spirit within me.”

Whatever his reasons, the broken engagement became a defining moment in Kierkegaard’s life and work. The experience of renouncing his love for Regine—while continuing to love her—became a template for understanding religious sacrifice and the “teleological suspension of the ethical” that he explored in Fear and Trembling. Many scholars see echoes of his relationship with Regine throughout his writings, particularly in his discussions of marriage, commitment, and the tension between aesthetic and ethical existence.

Regine herself eventually married Johan Frederik Schlegel and moved with him to the Danish West Indies. Kierkegaard never married, though he maintained a lifelong emotional connection to Regine. In his will, he left all his possessions to her—a gesture she declined, accepting only a few personal mementos.

Criticism of the Danish Church

Another significant struggle in Kierkegaard’s life was his increasingly antagonistic relationship with the Danish People’s Church (the state Lutheran church). Though raised in a devoutly Christian household and trained in theology, Kierkegaard became increasingly critical of institutional Christianity as he saw it practiced in Denmark.

His critique centered on what he perceived as the comfortable complacency of Danish church life. In Kierkegaard’s view, the church had domesticated the radical demands of Christian faith, reducing it to a respectable cultural identity rather than a passionate, existential commitment. The church’s close alliance with the state particularly troubled him, as did the tendency of clergy to live as comfortable civil servants rather than as witnesses to the challenging truths of Christianity.

This critique reached its climax in the last years of Kierkegaard’s life. When Bishop Jakob Peter Mynster died in 1854, and H.L. Martensen (Kierkegaard’s philosophical rival) eulogized him as a “witness to the truth,” Kierkegaard launched a blistering attack on the church establishment. Through a series of pamphlets titled The Moment and newspaper articles, he denounced what he saw as the hypocrisy and worldliness of the Danish church.

This final polemic consumed Kierkegaard’s energy in his last months. In November 1855, he collapsed on the street and was taken to Frederik’s Hospital, where he died on November 11 at the age of 42. The exact cause of his death remains uncertain, though it may have been related to a spinal disease or tuberculosis.

Pseudonymous Authorship Strategy

One of the most distinctive features of Kierkegaard’s literary output was his extensive use of pseudonyms. Rather than publishing directly under his own name, he created a series of fictional authors with distinct personalities, perspectives, and writing styles. These include Johannes de Silentio, Constantin Constantius, Johannes Climacus, Anti-Climacus, and many others.

This strategy of pseudonymous authorship was not merely a literary device but a philosophical method in its own right. Kierkegaard called it “indirect communication,” and it served several important purposes:

Alongside his pseudonymous works, Kierkegaard also published religious discourses under his own name. These “edifying discourses” were more directly Christian in content and tone than the pseudonymous writings. The relationship between these two streams of authorship—the pseudonymous and the signed—has been a subject of ongoing scholarly debate.

In his later reflections on his authorship, particularly in The Point of View for My Work as an Author (published posthumously), Kierkegaard insisted that all his writings, both pseudonymous and signed, served a unified religious purpose: to make people aware of what it means to be Christian in the deepest sense. Whether this retrospective interpretation fully captures the complexity of his authorial strategy remains an open question.

The Corsair Affair

A particularly painful episode in Kierkegaard’s life was his public humiliation in the satirical magazine The Corsair. In 1846, after publishing a deliberately provocative piece that invited the magazine’s attention, Kierkegaard became the target of a sustained campaign of mockery. The magazine published caricatures of his unusual physical appearance—his hunched back, uneven legs, and thin frame—and ridiculed his broken engagement to Regine.

This public mockery transformed Kierkegaard from a respected, if somewhat eccentric, intellectual into a figure of ridicule on the streets of Copenhagen. He later wrote that children would follow him, mimicking his awkward gait, and that he could no longer walk the streets without being laughed at.

The Corsair Affair deepened Kierkegaard’s sense of isolation and reinforced his critique of “the crowd” and public opinion. It also marked a turning point in his authorship, leading him to reflect more deeply on suffering, martyrdom, and the cost of authentic Christian witness.

Legacy and Impact

During his lifetime, Kierkegaard’s work received limited recognition beyond a small circle of Danish intellectuals. His dense, idiosyncratic writing style, his use of pseudonyms, and his polemical stance toward established institutions all contributed to his relative obscurity. Yet in the century following his death, his influence would spread far beyond Denmark to shape philosophical, theological, literary, and psychological thought across the globe.

Posthumous Recognition

The rediscovery of Kierkegaard began in the late 19th century, primarily through the efforts of Danish literary critic Georg Brandes, who published the first major study of Kierkegaard’s thought in 1877. Brandes, though not sympathetic to Kierkegaard’s religious views, recognized the philosophical significance of his work and helped introduce him to a broader European audience.

By the early 20th century, translations of Kierkegaard’s works began to appear in German, French, and English. The German translations were particularly influential, bringing Kierkegaard’s ideas into dialogue with emerging philosophical movements like phenomenology and existentialism.

The two World Wars and the social upheavals of the 20th century created a receptive environment for Kierkegaard’s emphasis on individual existence, anxiety, and the limitations of rational systems. As traditional certainties crumbled, his insights into the human condition seemed increasingly prophetic.

Influence on 20th-Century Existentialists

Kierkegaard’s most profound impact was on the existentialist movement that emerged in the mid-20th century. Philosophers like Jean-Paul Sartre, Albert Camus, and Simone de Beauvoir, though developing secular versions of existentialism, acknowledged their debt to Kierkegaard’s pioneering focus on individual existence, freedom, and authenticity.

Martin Heidegger, whose Being and Time (1927) revolutionized phenomenological philosophy, drew heavily on Kierkegaard’s analyses of anxiety, authenticity, and temporality. Though Heidegger rarely cited Kierkegaard explicitly, scholars have identified numerous conceptual parallels between their works.

“The truth is a snare: you cannot have it, without being caught. You cannot have the truth in such a way that you catch it, but only in such a way that it catches you.”

In theology, Kierkegaard’s critique of cultural Christianity and his emphasis on personal faith influenced figures like Karl Barth, Rudolf Bultmann, and Paul Tillich. Barth’s “dialectical theology,” with its emphasis on the radical otherness of God and the impossibility of approaching divine truth through human reason alone, shows clear Kierkegaardian influences.

Jewish thinkers like Martin Buber and Emmanuel Levinas also engaged deeply with Kierkegaard, finding in his work resources for thinking about the dialogical nature of religious existence and the ethical demands of encountering the Other.

Relevance in Modern Psychology and Theology

Beyond philosophy, Kierkegaard’s influence has extended into psychology, literature, and cultural criticism. His psychological analyses of anxiety, despair, and selfhood anticipated many developments in 20th-century psychology, particularly existential psychology and aspects of psychoanalysis.

Psychologists and psychiatrists like Rollo May, Viktor Frankl, and R.D. Laing drew on Kierkegaard’s insights to develop therapeutic approaches that addressed existential concerns rather than merely treating symptoms. Kierkegaard’s understanding of anxiety as both a burden and an opportunity for growth has been particularly influential in psychological theory and practice.

In literature, Kierkegaard’s influence can be traced in the works of writers as diverse as Franz Kafka, Rainer Maria Rilke, Walker Percy, John Updike, and Milan Kundera. His exploration of existential themes, his use of irony and paradox, and his emphasis on the individual’s struggle for authentic existence have resonated with generations of literary artists.

Contemporary Relevance

In our digital age, Kierkegaard’s critique of mass society, public opinion, and the leveling tendencies of modernity has taken on renewed relevance. His concerns about the “present age,” characterized by endless reflection without action, passionate interest in trivial matters, and the abdication of personal responsibility to “the public,” seem remarkably prescient in the era of social media and information overload.

Similarly, his insistence on the irreducible importance of individual existence and personal truth offers a counterpoint to various forms of collectivism, whether political, cultural, or technological. In a world increasingly dominated by algorithms, big data, and virtual identities, Kierkegaard’s defense of subjective inwardness provides resources for thinking about what it means to be authentically human.

Academic interest in Kierkegaard continues to flourish, with new translations, scholarly studies, and interpretations appearing regularly. The establishment of research centers like the Søren Kierkegaard Research Centre in Copenhagen and the Howard V. and Edna H. Hong Kierkegaard Library at St. Olaf College in Minnesota has facilitated ongoing engagement with his work.

Beyond academia, Kierkegaard’s insights continue to inspire individuals seeking to navigate the complexities of modern existence with integrity, passion, and authenticity. His vision of faith as a personal, existential commitment rather than mere intellectual assent speaks to those disillusioned with institutional religion but still drawn to spiritual questions.

Deepen Your Understanding of Kierkegaard

Explore the rich philosophical landscape of Søren Kierkegaard’s thought through his essential works. Begin your journey into existentialism with these foundational texts that have shaped modern philosophy, psychology, and theology.

Conclusion

Søren Kierkegaard’s life journey—from the melancholy-tinged religious household of his youth to his final polemical stand against the Danish church—embodied the very existential struggles he explored in his writings. His relatively short life produced an astonishing body of work that continues to challenge, provoke, and inspire readers across disciplines and generations.

Kierkegaard’s philosophical contributions are profound and far-reaching. His critique of Hegelian systematizing and his emphasis on subjective truth opened new pathways for philosophical inquiry beyond the constraints of rationalism and idealism. His exploration of concepts like anxiety, despair, and authenticity provided a vocabulary for understanding the human condition that remains relevant in our contemporary context.

“Life can only be understood backwards; but it must be lived forwards.”

As the “Father of Existentialism,” Kierkegaard pioneered an approach to philosophy that refused to separate thought from existence, theory from practice, or reflection from action. His insistence that the most important truths must be lived rather than merely contemplated challenges us to consider how our own philosophical commitments are embodied in our daily choices and relationships.

Perhaps most significantly, Kierkegaard’s work stands as a testament to the courage of individual conviction in the face of social pressure and conventional wisdom. His willingness to stand alone—against Hegelianism, against the Danish church establishment, against “the public”—exemplifies the authentic existence he advocated in his writings.

In an age of algorithmic thinking, mass culture, and digital distraction, Kierkegaard’s passionate defense of subjective inwardness and his critique of abstraction divorced from existence offer valuable resources for maintaining our humanity. His vision of faith as a personal, existential commitment rather than mere intellectual assent speaks to those seeking authentic spiritual engagement beyond institutional forms.

As we continue to grapple with the fundamental questions of human existence—questions of meaning, purpose, identity, and transcendence—Kierkegaard’s writings provide not answers but provocations, not systems but challenges, not conclusions but beginnings. In this sense, his work remains perpetually contemporary, inviting each new generation of readers to undertake their own existential journey toward authentic selfhood.

Begin Your Existential Journey

Discover how Kierkegaard’s revolutionary ideas can transform your understanding of existence, faith, and authentic living. His works continue to offer profound insights for navigating life’s most challenging questions.